These articles are part of a series compiled by Diana Wall for local magazines and newsletters.

Typhoid Fever Outbreak – 1846

“Our town is situated on a considerable elevation … our streets are wide, and the inhabitants tolerable cleanly (Sic) … and the place is proverbial for health. I have practised as a surgeon here for sixteen years and … I have no recollection of having had a single case of typhus (typhoid) fever. Within the last two months we have had upwards of 150.” Thus wrote Dr. Daniel Smith, a medical practitioner at Minchinhampton, in a letter to the newly formed Health of Towns Association in November 1846.

According to Dr. Smith, many hundreds of cartloads of dark soil, mixed with bones, were removed from the graveyard around Holy Trinity Church following the restoration of the building in 1842. This soil was thrown up into piles and anyone who wished could take it away for use in their gardens or on the fields around the town. Many cartloads were taken to the Rectory and used in the shrubbery, and Dr. Smith reported that the Rector’s wife and one of his two children died of the disease, along with the gardener.

A dispute ensued, between Dr. Smith and his supporters, and members of the local community, including David Ricardo of Gatcombe, who had either sanctioned the distribution of the soil, or used it and shown no signs of fever. This continued until the following year through letters, first to the “Gloucester Journal” and later to “The Times” and the “Daily News” in London. A.T. Playne, writing in the 1880s, ascribed the outbreak to the pollution of drinking water by “bacillus typhosus”, which he thought could live for a long period in contaminated soil. This would be washed down through the faults or “lizzens” in the rock, to emerge in the springs or wells that served the town. It is now more widely understood to be caused by cross contamination from faeces, caused by poor personal hygiene, but the outbreak of fever in Minchinhampton in the 1840s was an important catalyst for the setting up of proper drainage and water supplies in the whole of Gloucestershire. As an interesting postscript, Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, is thought to have died from typhoid fever. Vaccination became more freely available from the 1890s, and is now a disease more commonly found in the developing world.

********************

A Fearful Box – 1854

(From an article by the late Cyril Turk)

In early March 1854 the inhabitants of Box were anxious and fearful. Children had been roundly ordered not to go over the Common, women would not go out alone at night, and even the men were watchful. There was a good reason for this: three soldiers of the Scots Fusilier Guards stationed in Croydon had deserted the previous November and were now hiding on the Common, living according to the Stroud News “more like wild men than men accustomed to a civilised state”. In spite of the severe winter weather they slept in the open or in a sheltered hollow, so Box residents were afraid that they might become violent in their search for food.

Help was coming. On the 17th March, Police Sergeants Millard and Barton, with Constables White and Merriman, disguised themselves and took up separate stations on the Common. At 5.00 o’clock a suspected party of three entered the Old Lodge. Sgt. Barton cornered them in the kitchen and attempted to arrest one. A fierce fight ensued “tables were overturned and cups and saucers smashed”. The sergeant was saved by the arrival of the two constables and one deserter was captured and taken to ‘Hampton. The other two escaped, but at 11.00 o’clock were seen near the Bear Inn. A second one was caught; the other ran off pursued by Sgt. Millard who eventually closed sufficiently to deliver a blow to fell the final deserter. All three pleaded desperately for release, saying they would prefer suicide rather than a return to their regiment. (Perhaps this was a reflection on army life and the punishment for deserters?)

The press account does not say what happened to the three men after they left ‘Hampton, but Box could return to its former even tenor of life, broken only by family events and the occasional fracas.

********************

Let there Be Light! – 1857

“At a Meeting held in the Vestry Room on Friday evening the Sixth day of February 1857…. it was proposed: – That it is highly desirable that the streets of the Town should be lighted.” This is the first entry in the Gas Account Book for Minchinhampton, still owned by the Parish Council and in the care of the Local History Group. Without more ado a committee was formed to collect subscriptions and to seek tenders for the work and such was the enthusiasm of those present that £10.2s.6d (£10.13) was promised by the end of the meeting. It seems likely that word of the intentions of the meeting had already spread, because a week later two tenders had been received, and it was resolved that “Mr. S. Hill be employed to put up two specimen Lamps the one to burn oil, the other naphta (sic) The one Lamp to be placed against the Crown, the other upon Mr. Pearce’s House in Butt St., such lamps to be continued for one week.”

The trial period was successful and Solomon Hill was instructed to put up seven other lamps, for which he had tendered at 23s (£1.15) each. There were to be two in West End, one each in Well Hill, Tetbury Street, at the Cross, on the Market House and Mr. Simpkins’ house (possibly on the corner of King Street and Well Hill). Naphtha was the chosen fuel, and the charge for the winter of 1857/8 was 3d per lamp per night. By the following winter a further lamp in Butt Street was installed.

Other towns in the locality were being lit by gas, and as early as 1858 hopes were expressed that this might soon be the fuel for Minchinhampton. A parish meeting was held in the Vestry Room on 27th September 1859, with the Rector, Charles Whately, in the chair, when it was unanimously agreed, “That it is expedient that the Town of Minchinhampton should be lighted with Gas“. A new committee was formed, with full powers to put this into effect, as the Stroud Gas Light and Coke Company had extended its operations to the town. The lamps would be in the same places as before, and the cost still borne by public subscription.

The people of Minchinhampton were thus able to enjoy their streetlights during the winter months, but as was the case in those days, it was not felt necessary to light lamps during the summer. People’s lives were governed by the hours of natural daylight and retired to bed fairly early by today’s standards. A few years later it was noted the lamps were lit “from the 18th September to the 18th April …less six days at the full of each moon during the period, viz. 3 nights before the full, one night of the full and 2 nights after to cease lighting” for which the Gas Company would be paid the rate of £2 per lamp per annum. If the nights near the full moon were cloudy, then the Town was dark!

********************

The Provision of Allotments – 1895

The members of the new elected Minchinhampton Parish Council met for the first time on January 1st 1895. After the election of a Chairman (Rev. Albert Mather who was not an elected member!), and appointing a Clerk (William A. Jones) they moved to the business of providing services for the community.

The first administrative action was a matter mandated by the act that constituted parish councils – the provision of allotments. A committee of seven was set up, consisting of Messrs. J. Harman (farmer), J. Chamberlain (farmer of Box), A.E. Philpott (timber merchant of Brimscombe), T. Blake (timber yard foreman at Dye House Mills), C.C. Baglin (stone-cutter) and J. Hunt (publican of Amberley). These men were to ascertain who required allotments; applicants were to send to the Clerk in writing where they lived and how much land they needed. By 21st January some forty-one acres had been applied for, although there was only one applicant from Amberley. The Hampton Fields applicants said they would probably work in partnership.

Some land had already been laid out for allotments: just over two acres at the Glebe, which would be let to 30 applicants at 7d a perch (less than 3p), and five acres at West End to be let to 2 applicants at 6d a perch (2.½p). Perch was a linear measure of about 5 metres; it appears the plots would be of uniform width, although this is not stated. There was also three acres at Amberley, but it was deemed this was not required, and drops out of the record. A new committee was tasked to find land to make up the shortfall: J. Chamberlain and H. Milford (gentleman) for Box, J. Harman and W.G. Hill (baker of West End) for Hampton Fields and C. Baglin for Burleigh.

On 18th February it was reported that both Mr. A. T. Playne and Mr. H. G. Ricardo had agreed to let land for allotments, but the severe snowy weather prevented the members for inspecting the areas. It was September before the committee recommended accepting Mr. Ricardo’s offer of three acres of land at Park Corner, tenanted by Mr. Harman, at a rental of £19/10/- (£19.50). This would then be let to Burleigh and Walls Quarry ratepayers at 5d (just over 2p) a perch. In total two hundred letting forms were printed and Mr. Moody was appointed collector of rents.

The allotment rents were due each quarter day, but the collectors reduced this to January and June. There were constant references to defaulters in the early years, and a bonus system was introduced to prompt payers. It was a very imperfect system, with some holders working minute plots and others as much as two acres! However, Minchinhampton Parish Council continues to be the provider of allotments to this day.

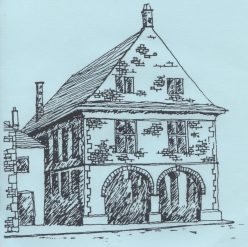

The Vestry Room

Minchinhampton Parish Council met for the first time on January 1st 1895, a new, elected body taking over from the Vestry, a group of influential citizens who had previously administered local affairs. The first M.P.C. Chairman was the Rev. Frank Mather (who was not actually an elected councillor!!) and he opened the proceedings by stating that the Vestry Buildings, where the meeting was being held, had been the property of the Vestry, who had purchased the site for £100 in 1818. The building had been erected for £300, the cost being defrayed by parishioners. (The records show that it was actually purchased on 13th October 1817, and that part of the building was already usable as the Vestry moved their meetings there from the top room at The Crown). Therefore, argued Rev. Mather, the Vestry Room and the adjoining house were parish property and belonged to the Parish Council. It was agreed that the churchwardens could use the room for church meetings, provided it was not needed for Council use, at a payment of 5/- (25p) a year, with a further 6d for fires to be lit.

The early Parish Council kept a careful watch on their property. Repairs were carried out in 1895, and in 1899 they accepted an estimate of £27/17/6d for further building work which included opening up an old fireplace. Complaints had been received about the odour from the privy at the cottage, and it was connected, with the two adjoining properties, to the main sewer. When a new sexton was appointed in 1895 the rent holy trinity church for the cottage was £3 per annum.

The first Clerk to the Parish Council was W.A. Jones and he was instructed to make an inventory of the furniture in the Vestry Room, which is minuted as consisting of one desk, one oak table, the parish map and three benefit tables. These latter small tables were used in the collection of money; in 1901 the Overseer was allowed to use the room “being parish property” for collecting rates. In 1896 an order was placed for 18 armchairs “the same as those in the Board room at Stroud” and a table with linoleum for the floor. The chairs and the table (with two extra drawers inserted in 1901) are in use today. In March 1895 the Clerk reported that he had “two cartloads of parish paper” and needed something so that he could put his hand on any paper directly. The Council therefore ordered a pitch pine cupboard, to be made by Mr. W.A. Harman for £3/10/0d with a deal back and brass fittings. This too is still in the Vestry Room.

Lighting and heating were two other creature comforts provided in the latter years of the C19th. Gas was laid on in 1895, and enabled both storeys of the building to be lit, as well as the external stairs. Open fires were very time-consuming for the caretaker, so in 1901 it was decided to purchase two second-hand gas stoves from the school, at a total cost of £3, and to put one in the Vestry Room and one in “the outer vestry”.

A series of inscribed boards, relating the charity bequests to Minchinhampton, are mounted on two walls of the Vestry Room. These used to be hung in Holy Trinity Church, but were probably moved to their present position early in the last century, when the walls of the nave and chancel were re-plastered. Other historical boards area also displayed – the record of the early Bowstead Medal winners from the school and the Fire Brigade boards from the Market House. These do somewhat darken the room, even with modern electric light.

The current Parish Council has continued to maintain and improve this old building. It was re-floored in the 1990s, electric heating installed, and Ron Chew constructed a display alcove for items. A few years ago four upper windows were re-framed and the leaded lights replaced by Graham Dowding, the notable local expert. The interior has been redecorated, new curtains hung at the windows, and the whole thoroughly cleaned. Once the Parish Council Meetings were moved to the Trap House, the room was used for various training courses, and currently is the home of the recording studio for “Five Valley Sounds” – the local talking newspaper for the blind.