THE LAMMAS

Peter Grover

William the Conqueror and his wife Matilda presented the Saxon manor of Hampton to the Convent of the Holy Trinity at Caen in Normandy, as part of the spoils of war. The nunnery in Caen was dedicated on June 18th 1066 on the eve of William’s invasion of England. He was Duke of Normandy and it was regarded in a special sense as a ducal family religious house, known as L’Abbaye aux Dames. In the course of time Hampton came to be called Minchen – Hampton, mynchen being the Saxon word for nun.

The ancient manor house acquired by the nuns stood on the site of the present house, “The Lammas”, or very near, possibly where the present tennis court stands. Contrary to popular local myth, however, the nuns never established a nunnery or cell of the abbey in Minchinhampton. They were in fact absentee landlords, deriving a considerable income from the rents and tithes, often paid in kind. There are records of cheeses and flitches of bacon being transported to Southampton to be shipped to Caen. The Minchinhampton revenues were specifically allocated to the upkeep of the Abbey kitchens and the entertainment of guests.

Successive Abbesses visited their property from time to time, usually staying at Bristol or Gloucester where there were substantial abbeys. In 1213 the Abbess purchased the right to hold a market and two annual fairs, thus making Minchinhampton a town – a distinction that it holds to the present day. The right was reaffirmed in the surviving Charter of 1269.

As Lords of the Manor, the Abbesses, through their representatives, were also empowered to hold courts and to mete out punishments to offenders. A bailiff, who was sometimes a Frenchman, administered the Abbey’s affairs and frequent disputes and lawsuits broke out between tenants and landlord, making the bailiff an unpopular figure. The existence of Minchinhampton Common has been attributed to the independence of the local inhabitants, and their tenacity in upholding their rights. The nuns built the parish church at Minchinhampton, naturally dedicating it to the Holy Trinity. The Abbey records also refer to regular payments for keeping a light burning in the chapel of St. Mary.

In approximately 1290 part of the manor was leased by the Abbey to Robert de la Mare, who died in 1308, a year after the accession of Edward II, who was brutally murdered at Berkeley Castle, and is buried in Gloucester Cathedral. Robert bequeathed the remaining lease to his son, Sir Peter de la Mare, and it was around this time that the property became known as Delamere Manor, contracted, as was the custom of the time with so many names, to “Lamers”. The first day of August is also known as Lammas Day, formerly observed as a Harvest Festival, but it is difficult to see the connection in relation to the property in Minchinhampton.

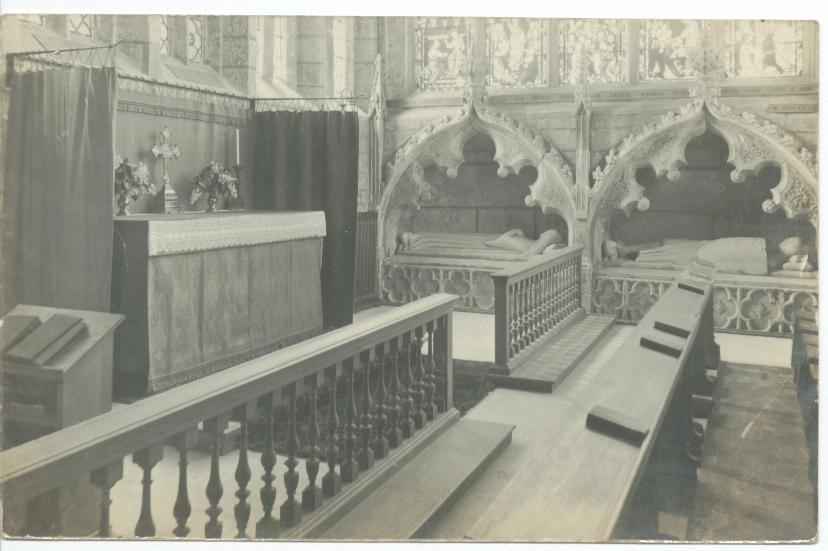

Sir Peter built the magnificent South Transept of Minchinhampton Church, with its Rose Window, probably as a Lady Chapel, or the chapel of St. Mary where the light was kept burning. St. Peter and his wife are buried in canopied tombs beneath the south wall, the arms on his shield corresponding with an heraldic tile on the west wall. (Minchinhampton and Avening, A.T. Playne, 1915) Other authorities have suggested the effigies may be of John of Ansley and his wife Lucy who held Delamere’s Manor at some point in the C14th. (Buildings of Gloucestershire, David Verey & Alan Brooks, 1999)

In 1483, at the accession of Richard III, Delamere Manor, now known as Lamberts or Lambards, was granted to George Nevile Esq. and his heirs. The house was described as “being near the spring at Minchinhampton”. This is presumably the spring which emerges halfway down Well Hill and which formerly drove a grindstone for sharpening shears and implements connected with the wool trade that thrived in the district. (Minchinhampton & Avening, A.T. Playne, 1915) Another spring flows from the wall below “The Lammas” and feeds a fishpond for the use of the house. The outline of a second pond can be seen at the foot of the field below the house, which was also used as a vineyard, the ridges still being traceable. Each of these springs issues from the junction between the permeable Oolitic Limestone and the Fullers Earth beneath.

The Norman nuns held Minchinhampton for 333 years, being finally disposed by an Act of Parliament in 1415 when the Crown confiscated all foreign-held ecclesiastical assets. England was at war with France (it was the year of Agincourt) and the King, Henry V, was naturally resentful that the revenues of French possessions in England were going to his country’s enemies. However, the newly acquired assets were not used for war-like purposes but were passed on to English religious houses, or used to found new ones. A life tenancy was granted to a friend of the king, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, and his wife Alice, and on their deaths the manor of Minchinhampton was presented to the Bridgettine Abbey of Syon, at Isleworth in Middlesex. The nuns of Syon remained in possession until 1534, with the dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII. The nuns fled abroad and their abbey eventually became the property of the Dukes of Northumberland, who occupy it to this day as Syon House. The Order eventually returned to England, and is still established at Chudleigh in Devon.

Henry VIII retained possession of Minchinhampton for a few years, together with the Manor of Avening, but in 1543 transferred them to Andrew, First Baron Windsor, in exchange for his manor at Stanwell in Middlesex. This adjoined the royal hunting grounds at Windsor, and was coveted by the King as an addition to the royal possessions. Baron Windsor, who was no relation to the present Royal Family, who adopted the name in the C2Oth, was not best pleased with the arrangement, but it was clearly an offer he could not refuse. A C17th historian describes the transaction in these words: “Henry VIII sent Lord Windsor a message that he would dine with him, and at the appointed time His Majesty arrived and was received with bountiful and loyal hospitality. On leaving Stanwell His Majesty addresses his host with words, which breathe the very spirit of Ahab. He told Lord Windsor: “that he liked so well of that place that he resolved to have it, but not without a more beneficial exchange.” Lord Windsor answered that he hoped His Highness was not in earnest. He pleaded that Stanwell had been the site of his ancestors for many ages, and begged that His Majesty would not take it from him. The King replied that it must be so. With a stern countenance he commanded Lord Windsor, upon his allegiance, to go speedily to the Attorney General, who should more fully inform him of the Royal pleasure.

“Lord Windsor obeyed his imperious master and found the draught already made of a conveyance in exchange for Stanwell, of lands in Worcestershire and Gloucestershire, and amongst them of the impropriate rectory of Minchinhampton and a residence adjoining the town. (The Lammas). Lord Windsor submitted to the enforced banishment, but it broke his heart. Being ordered to quit Stanwell immediately, he left there the provisions laid in for the keeping of his wonted Christmas hospitality, declaring with a spirit more prince-like than the treatment he had received, that “they should not find it Bare Stanwell”. (Baronage of England, Dugdale, 1675-6). Whether he found similar provisions laid in at The Lammas is not recorded, but he did not live long to enjoy his new home and died the following March. To rub salt into the wound he was also ordered to hand over a makeweight payment of £2,297.5s.8d. to the King.

In the C18th the Gloucestershire historian Ralph Bigland wrote: “The ancient manorial house inhabited by the Wyndesours is said to have been situate in the centre of the town and to have been very spacious and to have had hanging gardens open to the south.” (Historical, Monumental and Genealogical Collections relative to the County of Gloucester, R. Bigland, 1791) The hanging gardens probably consisted of the two long parallel terraces, which now form part of the gardens of “Lammas Park” and “St. Francis”, the two houses built in the grounds in the 1940s. On the lower of the terraces at the former there is the entrance to a tunnel, now blocked, which is said to have been connected to buildings on the other side of what is now New Road, and to have been used to convey grapes from the vineyard to be made into wine.

In 1790 the head lease of “The Lammas” was put up for auction at the Fleece Inn, Cirencester, but it was apparently unsold. The sale particulars describe it as: “that beautiful and delightful spot called the Lammas, consisting of a dwelling house, garden, fish ponds, pleasure grounds etc.”

Earlier, in 1651, the property had been acquired by the Sheppard family from the Windsor Trustees. Under the ownership of Philip Sheppard, who died in 1713, the Lammas ceased to be the manor house, the Sheppards preferring to live in the ancient house adjoining the church, which had been the headquarters of the Abbey of Caen’s bailiff or firmarius (from which the word farm derives). The Sheppards considerably rebuilt the old house, but Edward Sheppard, who died in 1803, did not consider it grand enough, and built Gatcombe Park, which then became the manor house of Minchinhampton. The old house was bought by William Whitehead, an eccentric character who pulled it down and laid the foundations of a very large house to be called “Minchinhampton Abbey”. He then ran out of money and the new house never rose above the foundations, which lie under the present school.

Meanwhile, the Lammas was acquired by the Pinfold family, a substantial family of clothiers and mill owners, who operated Longfords Mill, in the Avening valley, among others. Alice, daughter of Richard Pinfold, married an unpleasant character named Jeremy Buck of Minchinhampton, a captain in the Parliamentary Army, whose men beat the Royalist rector of Minchinhampton with pole-axes in front of his wife and children. ( Sufferings of the Clergy, Walker, post 1685) According to a local legend a group of Royalist troops took refuge in the spacious cellars of The Lammas, but on the approach of the Parliamentarians, they fled through a tunnel to the Church, where they were butchered. If this legend has a basis in fact the Pinfolds must also have been Royalists, causing some dissent in the family.

The Pinfold crest of three doves still stands over the main entrance to The Lammas, and the proposed sale in 1790 already referred to, was “expectant on the decease of the survivor of the Miss Pinfolds”. (Minchinhampton & Avening, A.T. Playne, 1915) These were two elderly spinster sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, who passed on their property in an unusual and charming way. Whilst walking to church one Sunday they were jeered by some local youth. The newly appointed curate, the Rev. William Cockin, came to their rescue and escorted them to church. This kindly act so impressed them that they agreed to leave all their possessions, including The Lammas, to the clergyman. On the death of the last of the old ladies the representative of the Pinfold next-of-kin contested the will, but was defeated.

Lord Erskine, the attorney who represented Rev. Cockin at the hearing, described what happened: “Two old maids in a country town, being quizzical in their dress and demeanour, were not infrequently the sport of the idle boys in the market place, and being so beset on their way to Church, a young curate, who had just been appointed there, reproved the urchins as he passed in his gown and cassock and, offering an arm to each of the ladies, conducted them triumphantly into their pew near the pulpit. A great intimacy followed and dying not long afterwards they left him all they had. The will was disputed, and when I rose in my place to establish it I related the story and said: ‘Such, gentlemen of the jury, is the value of small courtesies.’”

It would probably be unjust to suggest that the reverend gentleman may have dropped hints on his frequent visits, but he was certainly a wily character, judging by the way he progressed from being curate to rector. This he did by the simple expedient of betting the solicitor acting for the patron of the living £1000 that he would not appoint him! (Minchinhampton & Avening, A.T. Playne, 1915)

Architects date the present house at c1800, which would have been during Cockin’s curacy. The house is “of ashlar, with cornice and blocking course. South front of two bays and seven (sic) windows, with a central semi-circular porch on Tuscan columns supporting a broad bow window above. In the hall some pretty moulded plasterwork with Cockin’s (sic) coat of arms; other rooms have good plaster cornices.” (Buildings of Gloucestershire, David Verey & Alan Brooks, 1999) The Georgian front bears a striking resemblance to nearby Atcombe court at Woodchester and Barton End Hall, Horsley, and they were probably the work of the same local architect, possibly William Keck. The coat-of-arms already referred to is definitely that of the Pinfolds – was this part of an earlier dwelling, or inserted in recognition of the gift of the house?

Cockin became rector in 1806 and was well loved, though worldly, and his parishioners tolerated good-humouredly with his practice of rebuking them by name in his sermons if he considered they had misbehaved. He kept a generous table at the Lammas, which served as his rectory, and after dinner sat round a blazing log fire with his cronies, in locally made high-backed ‘beehive’ chairs, sipping port, of which he was a connoisseur. He died in 1841, aged 76, and the sale of his effects, including the contents of his cellar, lasted eight days.

Mr. C.R. Baynes bought the Lammas from Cockin’s heir in 1876, and the property remained with the Baynes family until the late 1930s. Charles Robert Baynes was a former member of the East India Company, later becoming a judge in the High Court in Madras, finally retiring in 1859 when the administration of the sub-continent was taken over by the Crown. “Change of scene with him meant only change of work”. (Holy Trinity Parish Magazine, 1899) He started the ‘Stroud News and Gloster Advertiser’ in 1867, directing it through its early days until 1873. He was active in Minchinhampton too, “with … Mr. Oldfield he was largely instrumental in building the (Minchinhampton) schools” (Holy Trinity Parish Magazine, 1899) as well as being an Inspector for the Lighting District and a founder member of the Fire Brigade Committee, both of which existed in the days before the Parish Council took over local affairs. In 1896 it was reported: “Minchinhampton Fire Brigade proceeded to the Lammas … the men were put through several drills by Capt. Wess and an experiment with the jumping sheet was tried. Capt. Baynes, grandson of Mr. Baynes, jumped from a second storey window of the house and successfully landed in the sheet.” (G.R.O. P217a PC1/1 &2/2) A talented and polished speaker, and a staunch conservative, he was married twice, with four sons and four daughters. C.R. Baynes died in 1899, in his 90th year and was buried in Amberley churchyard alongside his second wife, Maria Dyneley, but there is a memorial window in Minchinhampton Church. (Minchinhampton & Avening, A.T. Playne, 1915) Miss Mabel Baynes was a great benefactress to the Minchinhampton Schools, and sometimes taught needlework to the girls. (Minchinhampton Life and Times, Volume 2, 2000)

Subsequent owners of the Lammas included Mr. A.H. Fyffe, Mrs. Harcourt Wood, Mr. Ordway and Mr. J. Oldacre. In 1977 Mr. G. V. Sherren, then Mr. Arne Larsson in 1985, bought it and Lord & Lady Catto purchased the property in 1988.

Visitors to the Lammas often remark on the unobtrusive nature of the entrances to the house. Its parkland to the west was sold off in the 1930s, and the original gateway and drive now form the entrance to “St. Francis” and “Lammas Park”. The celebrated architect, Sir Peter Falconer, built the former in 1949, and the grounds contain an icehouse dated 1768, and a modern summerhouse, modelled on that at Longfords House. The cottage opposite the gate was built for a gardener or lodge-keeper. Of the remaining buildings, the barn to the north of the house is said by the Department of the Environment in their latest register to date from the C18th, but it could be earlier. (The Lammas is Grade II*). The inglenook fireplace is a C20th insertion, and the stables and coach house date from the early C19th.

When Holy Trinity Church was largely rebuilt in 1842 a number of incised stone slabs were found built into the nave walls. They were probably memorial slabs over graves, and had been used by the C14th builders when they rebuilt the Saxon or Norman church. A similar stone can be found in the northeast wall of the cottage attached to the main house. Three more have been recovered from the bridge over the sunken lane. The three bridges were probably made because there was an ancient right of way through the park and pedestrians could now use it without seeing the grounds of the Lammas, and being invisible themselves from the house. The lane now marks the western boundary of The Lammas grounds.

********************

LONGFORD’S LAKE (or Gatcombe Water)

This landmark has celebrated its bicentenary, for it was in 1806 that William and Peter Playne, of Longford’s Mill, conceived the idea of damming the Avening Stream and the smaller feeder springs to create a large pond, storing water to turn the waterwheels. Although there was probably a steam engine at the mill by this date (the early records of Longford’s were lost in a fire) water was still the cheapest form of motive power, especially when coal had to be imported from the Midlands. The only pond was a much smaller one, which provided a head of water for Iron Mills.

The dam, over 100 metres in length and 10 metres high, has a wide wall of stone at its heart; this was faced with puddled (compressed) clay, and the whole covered with an earth mound. The cost of construction was £945, which seems a cheap price for a work of that size. It has never given any cause for concern, although the brothers did not build their new sheds immediately below the dam, preferring instead to carry the water to the wheels via a canal that A.T. Playne, writing in 1915, said, “constantly requires repair, and has been a perpetual expense to keep in order.”

During the filling of the new lake, little water was allowed to flow downstream, causing opposition from other mill-owners, but once the long-term benefits were recognised, this opposition dwindled away. Some land to be flooded had to be purchased from Philip Sheppard, owner of Gatcombe; he would be amused to know that the Ordnance Survey insist on naming it Gatcombe Water rather than Longford’s Lake! Once complete, the recreational benefits of the lake were recognised; it was stocked with trout and roach, and three boathouses were built on the banks. A vista was opened up from Longford’s House, which allowed the lake to be seen from the terrace.

The dam has twice assumed a strategic importance; in the machine-breaking riots of the 1820s it was guarded day and night, as the handloom weavers threatened to breach the dam to sweep away all the mills to Nailsworth and beyond. In an echo of this, the Longford’s Platoon of the Home Guard was formed during World War II and carried out nightly patrols to prevent enemy sabotage, receiving extra rations of tea and sugar in return! Thankfully, the dam remained intact, and the lake, although somewhat silted at the Avening end, is still a landmark that can be enjoyed by the people of the area.

********************

THE LONGSTONE, HAMPTON FIELDS

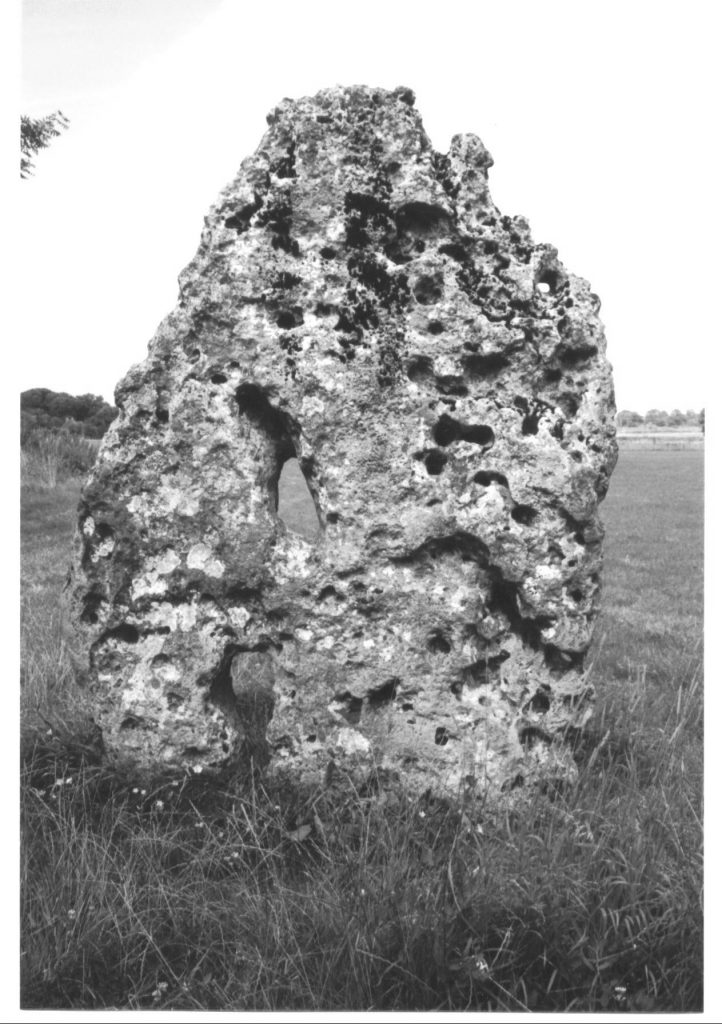

This is certainly one of the oldest landmarks in the Parish of Minchinhampton – but just how old? It you want to be really correct the answer is 140 to 190 million years, which is how long ago the Jurassic Oolitic Limestone was formed, in clear sub-tropical seas like those of the Caribbean today. The Longstone comprises what is locally called “holey” or “ragged” stone, found just below the surface soil, seen in some cottages, and the Ragged Cot Inn.

But this is not just an isolated piece of rock left by weathering; man has erected it for a purpose. There are two main theories about what the Longstone is. Firstly, it could be all that remains of a Neolithic long barrow, a burial mound similar to Whitfield’s Tump on the Common and others at Avening and Rodmarton. If this were the case, then the stone would date from between 3500 and 2500 B.C. There does appear to be another large stone incorporated into a field wall close by the Longstone, which might support this theory.

However, Timothy Darvill in his book “Prehistoric Gloucestershire” thinks that this is unlikely, as it seems odd that some barrows have been worn away, and others carefully preserved. He uses the example of the Tingle Stone, standing near the Longstone, which sits on top of a long barrow and suggests that these standing stones date from the Bronze Age, 1600 to 700 B.C. each marking a small cemetery of that date. This is when round barrow burials were in use, as can be seen alongside the Cirencester Road at Hyde, but it could be that these were smaller, individual or family graves with no mound, clustered around the standing stone, which is in a fairly elevated position on flat ground.

At present the stone stands over 2 metres in height, and could, of course, have been moved since it was first erected. The land here was part of the open field system of the Manor, and “Longstone Field” appears on many old maps and deeds. In the days of oxen ploughing teams, it seems most likely that furrows would go around the stone, rather than move it, and the fact that this area retained strip farming into the C19th might account for its odd position in relation to the stone walls and gate.

Some interesting legends are attached to the stone, as with many similar ones elsewhere. In 1887 there was a description of “a perforation through which children used to be passed for either cure or prevention of measles, whooping cough and other infantile ailments. Similar stones in Cornwall are said to be employed in the same way, as also in India” (Gloucestershire Notes and Queries) A.E. Playne also mentioned that the stone had the ability to cure ricketts. A more gruesome variation is that babies who were small enough to be passed through the hole would be killed – the reality is probably that they would be so small that they would not survive babyhood.

Like many other stones the Longstone is supposed to get up and walk around its field at midnight on Midsummer’s Night. In Victorian times this was altered to dancing every night on hearing the church clock strike midnight – although the clock was only installed in 1897! Perhaps a little too much to drink at Hollybush, then an inn, might account for this tale. One other enduring story is that the Longstone and Tingle Stone were quarried from the Devils’ Churchyard, although I have seen no geological evidence that this is so. It seems a considerable distance for prehistoric times, although evidence from Avebury and Stonehenge show that movement of slabs was quite possible. In any event, it is a nice way of linking two historic and “magical” sites.

********************

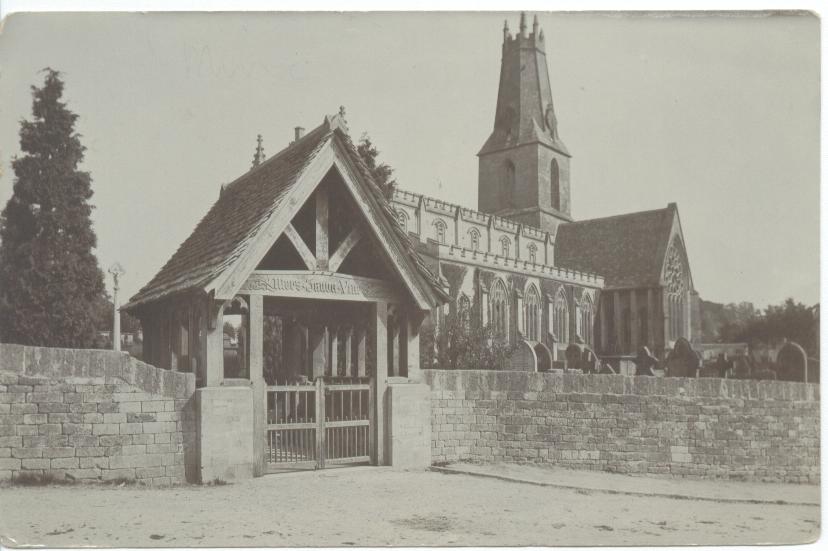

THE LYCH GATE

The main entrance to Holy Trinity Churchyard from Bell Lane is via the roofed lych gate. The name comes from the Old English “lic” meaning body or corpse; this was any gate in the wall of a graveyard, where a coffin was met by the clergy and prayers said in preparation for the burial service in church. In Minchinhampton, before the early years of the twentieth century, the mourners and clergy stood outside, unprotected from the elements. The wheeled bier was an important part of the ceremonial, especially if the deceased had lived in Box or Hyde, and it is preserved in one of the vestries, along with the blue and black bier cover. By 1909, however, the present roofed structure had replaced the earlier double gate “that could not be called beautiful.”

The Stroud News of 18th June 1909 reports the formal opening of the gate. “The lich-gate (sic), which was constructed by Mr. Wm. Harman, to a design prepared by a brother of the Rector, the Rev. E. Lonsdale Bryans, is of local stone so far as the tiles of the roof and the foundations are concerned, the seats and floor being of blue pennant stone. Throughout the structure old English oak has been used from the famous Market House and the Church, and some of it is reputed to be between 200 and 300 years old”. Assuming the last sentence to be correct, the Edwardians were therefore keen on recycling, and William Harman, as the foremost builder in the town, would have been well placed to store and reuse materials. The article gives the cost of the gate as “about £120”, raised by public subscription as explained by an inscription under the roof “A.D. In Memory of Edward Playne, 1909 Mors Janua Vitae”. (The Latin translates as “The door to death or life”) But this was far more than a memorial to a good Anglican; all sections of the community had been involved in raising funds, in choosing to erect a suitable memorial (the gate rather than a fountain, bandstand or indeed a house for the parish nurse) and in the actual construction. So who was this Edward Playne who inspired such affection?

Born into one of the well-known local clothier families, Edward Playne lived with his wife and family at “Springfield”, on New Road. He had died in 1907, aged 62, and “from his early manhood had thrown himself into active work on behalf of the public good”. He had been one of the first County Councillors in Gloucestershire, serving from 1892, and as an experienced local politician oversaw the election of the first Parish Council in Minchinhampton in 1894. It is interesting to note that under the Local Government Act women were permitted to vote for parish councillors, or even stand themselves, but at the meeting in the Market House only men were present and voted by a show of hands. After the first vote, a poll was called, the same thirteen Conservative candidates being successful and taking office at the meeting on January 1st 1895. Edward Playne himself became a councillor later, and served as Chairman until his death and he also served on the Market House Committee and the Committee of Commoners, an echo of public life today.

Perhaps his greatest contribution was his membership of the Stroud Board of Guardians, the body that might best be described as the Social Services of the Victorian age, charged with alleviating hardship at a time when local industries were in decline. He had served on the Board all his adult life, eventually becoming Chairman in 1889. It was this, perhaps more than any of his other public offices, which so endeared him to the workingman in Minchinhampton, and to the congregation of the Baptist Chapel as much as to that of Holy Trinity. The lych gate was seen as a symbol of the juxtaposition, rather than union, of established church and the town, and it was one of the elders of the Chapel, speaking at the dedication who said, … “the rising generation would make enquiries as to why the gate had been erected, and they would learn that Minchinhampton produced one of the noblest and one of the best men who ever lived.”

********************

MOOR COURT, AMBERLEY

Once the leaves fall from the trees, it is possible once again to see the main façade of Moor Court, on the northwest side of Minchinhampton Common. This landmark is hidden for most of the year by the mature oaks and beeches that remain from its once extensive gardens, with only the Victorian lodge house as a clue to what lies beyond.

The present Moor Court probably dates from 1864, although there is a reference in the Stroud Journal of 1855 to the sale of a “recently built” property. Perhaps this was just an updating of the much older house, which lay at the heart of what was then known as the Mugmore Estate. This enclosure was certainly in existence when the mediaeval custumals of the Manor of Minchinhampton were drawn up, detailing the duties of the population of this part of Gloucestershire. Some authorities believe “Mugmore” came from an Old English name – Mucga – but it could also be derived from moccas meaning a pig, and thus mean the place where there was pasture for the Manor swine. Whatever the derivation, “Muggemore” was a location recognised as distinct by A.D.1300.

The estate of Mugmore, the largest in Amberley, continued in existence until well into the C19th, although there is no evidence of the appearance of the original house. In 1747 it formed part of the manor Estate, and was mentioned in the marriage settlements of Philip Sheppard. After his death it passed first to his widow Jane, then to their daughter Mary, who sold Mugmore in 1802. By 1839 the estate was in the hands of Joseph Hort, who then sold it on to Mary Lowsley, before her marriage to the Rev. Williams. (The Lowsley-Williams family eventually became established at Chavenage House.) It was Mary and George who had the present Moor Court built.

The architects they employed were the firm of Elmslie, Franey and Haddon who were based in Great Malvern, and designed several buildings there, although it is not clear just how they came to be used in this part of the Cotswolds. The house is in the Italianate style, with the most important feature being the porte-cochere on the entrance front, with two storeys above. The photograph shows the conical roof, triangular pediments and decorative ironwork. In the days of horse-drawn

transport, guests could arrive in their carriages and be set down without getting wet or windswept in inclement weather – an important point when the house was 250m above sea level! On the west the owners constructed a terrace, which still exists, outside the Drawing Room to take advantage of the views across the Nailsworth Valley.

On the garden façade “the centre … was rather weakly emphasised by a full- height canted bay window. Either side, flanking this, the elevation had a pair of Venetian windows. The attempted symmetry was somewhat corrupted by the service wing, slightly set back at the north end of the house” . (The Country Houses of Gloucestershire, Volume III, by Nicholas Kingsley and Michael Hill, 2001) In 1869 the first of two sales of estate land was held, comprising ten lots of land and twenty dwellings, and it is tempting to speculate that this was to recoup capital expended in the building of Moor Court. At some time between 1871 and 1876 Lord Charles Pelham Clinton purchased the house and truncated estate, and lived there until his death in 1894. Shortly afterwards, in 1897, the last of the estate land was sold, leaving just the house and its immediate gardens.

Older residents remember with affection the time that Moor Court was a hotel, catering for long-term residents, tourists and containing one of the premier function suites of the district. In “Village Voices” (Millennium Book Group of Amberley, 2000) John England related how his grandmother, Kate Webb, then running a guesthouse at Rose Cottage, purchased Moor Court for £4000 in 1938, from a building firm. During the war, not only did the hotel provide accommodation for people moving from the Home Counties, but also the grounds were used for fund-raising events for the war effort. Mr. England remembers Lady de Clifford, Norman Hartnell, Lady Baden-Powell and the novelist P.C. Wren all being associated with Moor Court Hotel. In 1944 Lady de Clifford chaired a meeting at Moor Court which resulted in the formation of the Minchinhampton branch of the Girls Training Corps.(Minchinhampton Life and Times, Volume 2, 2000) Mrs. Webb died soon after the war, her son and daughter ran the hotel, and gradually the pattern changed from longer-term residents to summer tourists and functions such as wedding receptions, dinner dances and the like. In 1975 a world recession, coupled with new fire regulations threatened the viability of the hotel and it was sold. The main house was converted into three dwellings, and a number of large houses were built in the grounds, but Moor Court remains one of the major landmarks of the Common.

********************

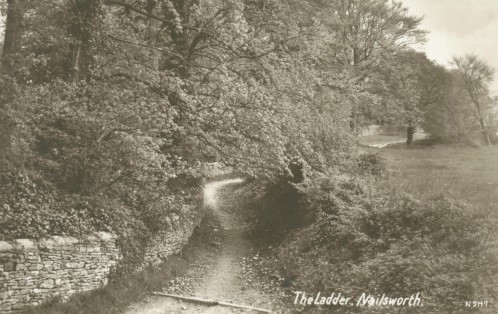

THE NAILSWORTH LADDER

Diana Wall

If you study an Ordnance Survey map of this area it is easy to pick out the road known as the “W”, running from Nailsworth to the Halfway Inn. Looking more carefully, you can see a track, which takes the direct route up the gradient – this is “The Nailsworth Ladder”. On the ground, its lower end at “The Hollies” is often overgrown, and easy to miss, but each February it is the scene of a motoring trial with its roots in the first years of the last century.

Before the C18th there were few roads of any permanence in this area, only tracks used by mules or horses and carts, whose route would vary according to the season. As one part became a quagmire, the carriers would move around it, or take a different track altogether. Routes came up from the valleys to the Common, and then down again on the other side, although the track from the Great Park towards Cirencester kept to the hill summit, along the line of the Old Common, later utilised for the turnpike road. The former Blue Boys Inn is aligned along this route, rather than the present-day road. The Ladder was one of the tracks up the hillside, from the scattered communities of Newmarket, Shortwood and Spring Hill. Similar routes included Ham Mill Lane, from the valley at Thrupp, Bownham Lane parallel to it, and Whips Lane at Amberley.

What was a suitable gradient for a horse or other pack animal was deemed too steep for carriages or coaches in the turnpike era. There is a maximum gradient of 1 in 2 ½ for the Ladder, with nothing on the current track less than 1 in 5. (according to Trevor Picken in A History of Hampton Cars, 1997)(The use of mules or donkeys on some of the steepest hills in the Stroud district is easily understood when these gradients are considered, and on Whips Lane there is a stone which local tradition suggest was the resting place for drovers and their loads.

In 1781 the Nailsworth Turnpike Trust discussed the building of what is now the ‘W’. This would link the newly-constructed Gloucester to Bath Turnpike with Minchinhampton via Hampton Green. By going along the contours, albeit with the series of bends from which the road takes its name, they obtained a gradient of 1 in 9 at the bottom and 1 in 12 at the top. The stone for the surface was to come from a quarry in Hazelwood, laid 12 inches deep in the middle decreasing to 6 inches at the sides, thus creating the camber necessary for drainage. The road was completed in six months and a toll-bar was erected at the bottom of the hill. Thus the Ladder became a bypassed track.

The concept of trials, for motorcycles and cars, has its origin in the early years of motoring. Just as now, manufacturers tried to show that their machines were superior to the others around. This might take the form of a long-distance road run, a high-speed timed trial or an ascent of a steep hill. In the early years of the C20th the horse was still supreme, and many of the road surfaces were less than suitable for mechanical transport. The area around Stroud, with its many steep hills and relatively sparse population was an ideal location for the testing of machines both by manufacturers and individuals.

One of the earliest cars to climb the Ladder was a 10-horsepower Hampton, which was then built in Birmingham. This factory later moved to Dudbridge, where the Sainsbury supermarket now stands. Hampton Cars commissioned some publicity shots of an attempted climb in 1914 , a few days after a formal manufacturers trial, when a Singer, Warren-Lambert and a Morgan were also successful. In the same way that high-speed trials evolved into grand-prix and endurance races in the post World War I period, so ascents of unsurfaced hills, linked by long-distance runs, developed into what are now known as “Classic Trials”. Speed was of little importance (although you would wish to finish in daylight!) but the varying terrain tested the machines reliability, as did the mileage covered. The Motor Cycling Club, which celebrated its centenary in 2001, ran events to Lands End and Exeter from starts all around the U.K. before 1910, although probably the routes did not come into the Stroud area. The annual “Nailsworth Ladder August Event” was very popular in the post-war years; Mrs. Lionel Martin was the first lady to make a clean climb in her husband’s Aston Martin in 1920. “10 – 16 H.P. Hampton, Complete – £520. The FIRST and ONLY car with 2, 3, and 4 passengers to climb the NAILSWORTH LADDER – a gradient of 1 in 2 ½. Can easily do 50 miles per hour.” So ran a 1920s advertisement for Hampton Cars.

The hey-day of trialling was probably the 1930s. “In the years immediately before the Second World War, which is the period of motor sport dealt with in this book, club racing…. was non-existent. Racing of any sort was confined to the old Brooklands track, the narrow parkland circuit at Donington, together with occasional forays at Crystal Palace. Because of this, the major pastime of the clubmen of those days was “Trials”. Major trials events used to attract entries nearly as large as are today received for race meetings at Silverstone, Goodwood or Brands. Entries usually consisted of only mildly modified (and up to 1938 “Knobbly tyre” equipped) versions of the small two-seater sports cars of the day“. C.A.N. May wrote this in the 1960s in the preface to the second edition of his book “Wheelspin” and also mentions that hills like Nailsworth Ladder and Ham Mill regularly attracted crowds of hundreds of spectators. In the early 1930s the M.G. Car Club ran “The Abingdon Trial”, taking its name from the Morris Garages factory, which was both start and finish of the event. A lunch halt was made at the Bear of Rodborough. May attempted the local hills for the first time in an M.G. J2 in 1933. “Composure was regained slightly after a successful non-stop climb of Nailsworth Ladder, because “The Ladder” which runs up from just outside Nailsworth directly on to Rodborough (sic) Common, and is steep, with a very rough surface of rock outcrop, had quite a reputation.” Such was the publicity generated that M.G. ran a works team for many years and the area would be used many times during the season, for both motorcycles and cars. These events were (and still are) totally different from a hill climb, which took place over a tarmac surface, against the clock, at venues like Prescott (north of Cheltenham) or Shelsley Walsh (Worcestershire). The Motor Cycling Club, now catering for cars as well as bikes, had also discovered the area: “For 1933 and 1934 the event (The Team Trial) again broke new ground, with the start in the Stroud Area – actually from the foot of the first section, Sandy Lane – and it was in this event that the names of well-known ‘trials hills’ began to appear: Sandy Lane itself, Bismore, Ferriscourt, Knapp, Nailsworth Ladder, and Catswood. The Ilkley and Birmingham M.C.C.s were the respective winners.” (The Motor Cycling Club, Peter Garnier, 1989)

World War II obviously intervened, but trials were the first type of motor sport to resume in this country, and on February 23rd 1946 the Bristol Motorcycle and Light Car Club ran their “Feddon Trial” which used both Nailsworth Ladder and Bownham Lane. For two years many pre-war drivers and cars competed in a full round of trials, all over the country, but the restrictions on fuel, together with the age of many of the vehicles, led to a pause until 1950. It was in that year that the Stroud and District Motor Club was formed. Three good friends, Philip Ford, Peter Hewins and Bob Parker, with others who had expressed an interest, met at the Bear Pools Cafe on 5th June to adopt a constitution. All three had been interested in pre-war car trials, and since that date the Club has maintained its focus as a trials club. In looking for a symbol for the whole district it was decided to adopt a silhouette of Rodborough Fort as the Club Badge.

Many of the early trials organised by the Club were single-venue events, but in 1955 there are records of using Nailsworth Ladder and Fort near Dursley. Of course, other clubs continued to use the local hills. Competitive sports cars, such as Dellows would compete alongside Volvos and Singers. The premier event “The Cotswold Clouds” was first run in the early 1960s, using both pre-war hills and other venues such as Ebworth Woods. In 1962 “Avening and the Ladder were too dry to claim many victims. Cakebread’s TR2 bottomed twice on the Ladder, but Dive’s Roche and Hadland’s Skoda made fast easy climbs. There were many spectators on the Ladder, and two old-timers were heard to say “It were rougher’n this in the old days” “Ah! And a damn sight steeper too””.(The Stroud & District Motor Club, ed. Nigel Moss, 2000) It is this event in early February that still attracts car competitors from all over the country, and a great number of spectators, to the top of Ham Mill, and along “the step” of the Ladder. It is the only event where cars are permitted to use these hills, although motorcycles also climb them during the “March Hare Trial”.

For most of the year the Ladder is a peaceful track, offering a steep climb to those walkers who enjoy the countryside above Nailsworth. The top section is now only a footpath, but once each year it is possible to participate in a spectacle little changed in seventy years. Long may its use continue!

********************

THE STONEHOUSE AND NAILSWORTH RAILWAY

Roy Close

On the 13th July, 1863 a newly-formed, independent Company, the Stonehouse and Nailsworth Railway Company, was authorised to build a line from the Midland Railway main line (Birmingham to Bristol) at Stonehouse, to the Cotswold market town of Nailsworth, following the Frome Valley as far as Stroud.

Earlier that year a notice in the 17th January edition of the Stroud Journal had announced the formation of the Company, by raising £65,000 in 3,250 shares of £20 each, the bulk of which would be raised by a number of prominent local businessmen, with the rest to be provided from subscriptions from the general public of the district, applications for which were to be made to G.B. Smith, Solicitors, of Nailsworth.

The decision to launch the Company had been taken after negotiations with the Midland Railway had resulted in agreement to go ahead; this after the original Bill for the line had been defeated, when a proposal to include a station at Woodchester had resulted in objections from shareholders, who thought it would encourage the use of the Catholic Convent on the edge of the village.

Although the eventual branch line was destined to become a rather sleepy railway backwater, the promoters originally had some rather grandiose ideas, mainly originating from the Midland Railway. They intended to continue the line beyond Nailsworth, crossing the Cotswolds via Tetbury and Malmesbury, and eventually terminating at Southampton, giving the Midland a route to the south coast, and the opportunity to cut across the heartland of the Great Western Railway.

Had these schemes come to fruition the railways of the area might well have been very different. Unfortunately however, the money ran out and the line never got beyond Nailsworth, where the terminus with its odd track layout remained to remind travellers of the ambitious but impossible scheme. It would have been very expensive to build, needing steep gradients and large earthworks, and the eventual size of the task was far beyond the funds and resources available at the time.

The original local committee consisted of the following prominent local citizens: William and Charles Playne, S.S. Marling, A.M. Flint, A.S. Leonard and J.E. Barnes, all in Cloth Manufacture, and Isaac Hillier, J.G. Frith and George Mills, who were in Provisions, Tea and Meal respectively. One assumes they would have held the majority of the shares.

The building of the line went ahead more or less as planned with stations at Stonehouse, Ryeford and Nailsworth, and several sidings along its route, serving cloth mills and other industries. It was eventually opened on February 1st 1867. Although no major earthworks were required, completion had been delayed through the failure of the contractors to meet deadlines and the constant slipping of bridges over canals and streams, which the track crossed and recrossed.

Although the turning of the first sod at Nailsworth by the M.P. the Hon. A Horseman in February 1864 had caused great excitement in the small town, with flags, bunting and a brass band, the opening of the line was generally low-key, apart from decorating the engine. There was some celebration in Nailsworth, with cannons being fired at High Beeches and the Subscription Rooms (later the cinema and now the Boys Club) while the band played in the streets as people celebrated.

There were three regular journeys between Nailsworth and Stonehouse at first, with a fourth added later that year, and in the early 1880s a fifth. The early trains ran between 8.00 a.m. and 8.30 p.m. with each journey taking approximately twenty minutes. After the opening of the Stroud branch, between the town and Dudbridge in 1886 (possibly later than was intended originally) services were increased to seven daily; the last ended at Stonehouse at around 9.00 p.m.

Despite these increases in passenger services, the line relied heavily on goods traffic, especially until the Stroud branch was opened. The large number of private wagons based at Nailsworth with at one time at least nine different firms being represented reflected this. The goods yard at Nailsworth was a busy place, containing a turntable, engine shed, goods shed, cattle dock and a large warehouse with several smaller buildings near the entrance from the town. The warehouse is still in regular use today, mainly as a timber store, and still carries the original name of C.W. Jones & Co.

The station buildings at Ryeford, Dudbridge and Nailsworth were all built to the Company’s own design, with walls of Cotswold stone and a grey slate roof. That at Nailsworth rather dominated the short platform, being much larger than those normally found on a small branch-line terminus, perhaps reflecting the main line status envisaged by the founders of the original plans. The meetings of the board of the original railway were hold there, in what later became the booking hall.

The original station at the Stonehouse end was probably only a small temporary affair and was replaced by one in the Midland Railway design of wood on a stone base with a stone chimney and a wide canopy. It was possibly built at the same time as the one at Stroud, when the additional branch from Dudbridge was completed in 1886. The one at Woodchester was also to Midland design but was much smaller, built rather as an afterthought and possibly influenced by letters in the press complaining of passengers having to walk to Dudbridge for trains.

These buildings underlined the backing given by the Midland Railway almost from the start and they were soon involved in supporting the line’s financial affairs, as these were fully stretched by debts incurred in its building. In 1869, for instance, the Stroudwater Canal Company were awarded over £1000 damages against them for interruptions to traffic on the canals whilst the bridges were being built. They were apparently unable to meet this until 1878, when they had been invested in the Midland and they were eventually dissolved as a separate company after the completion of the branch to Stroud in 1886, when the running of the complete line became the responsibility of the Midland.

The Stroud extension probably reprieved the passenger traffic on the line and also added to the goods traffic several lucrative contracts, including the supply of coal to the Stroud Gas Works. This continued until well after World War II, and at times was over 3000 tons of coal a month. Passenger trains consisted of four and six-wheeled coaches, drawn by locomotives such as the Kirtley 0-6-0 and Johnson 0-4-4 tank engines. Amongst the services provided were a number of excursions to Gloucester, Bristol and Birmingham, while the connection to the Midland main line at Stonehouse enabled many to have a day by the sea at Weston Super Mare, especially in later years. I well remember being taken on some of these just before World War II.

However, passenger services were gradually affected by the new local bus services, and despite combining passenger and goods services, by using one coach along with several trucks, they were temporarily suspended in 1947. They never resumed and by the middle of 1949 their departure was made official, but goods traffic remained fairly constant. Eventually the arrival of Dr. Beeching in the 1960’s sharpened the knife and the line finally closed in June 1966, almost, but not quite, reaching its centenary.

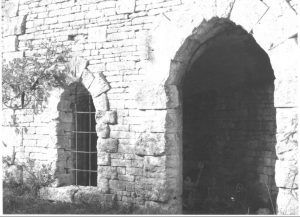

Today all the track has long-since disappeared, although its recent conversion to a combined walking and cycle track between the two original termini has meant that it still provides an amenity for the local people, although rather removed from the intentions of its founders nearly a century and a quarter ago. Some buildings still remain, particularly at Nailsworth, while at other places semi-derelict walls and other reminders can be seen amongst the undergrowth. Nailsworth has recently had a new fire station built almost on the entrance to the old goods yard.

The last scheduled passenger service ran on the 14th June 1947 when, although leaving Stonehouse empty, it was completely full after leaving Ryeford with passengers having to find room in the guards van and apparently some even travelled on the footplate. Amongst those embarking at Ryeford were some 60 boys from Wycliffe College and their Headmaster, Mr. Sibley.

At all the stations on both branches, and at other vantage points such as bridges and level crossings, it was cheered on by crowds of people all wishing to witness the historic journey. At Dudbridge detonators were let off, and the engine was suitably decorated with flags, bunting and greenery. At Nailsworth it was detached and backed along the rails to the water tower for replenishment before commencing its final run back to Stroud and Stonehouse.

Several excursions were run by the Gloucestershire Railway Society in the following years, culminating in a final one on the 7th July 1963 when three coaches, packed with passengers, were hauled by a 1934 L.M.S. 0-6-0 engine, specially brought down from Redditch for the occasion.

During its lifetime there were, obviously, a number of varied and unusual incidents, including a number of accidents, two of which caused fatalities. One occurred at Stroud when John Griffith, a carter of Stroud, was kicked by one of the two horses on his dray when he was driving for the L.M.S. in 1908. He was driving from the shafts (apparently not officially allowed) and the Coroner at the inquest recorded a verdict of accidental death, when he also praised the bravery of a witness, William Harrison of Brick Row, for pulling the victim clear of the shafts when the horses bolted.

Another tragic accident occurred, this time at Nailsworth, when a porter, Charles Paish, (52) of Horsley Road was engaged in shunting operations in the goods yard in November 1918. He was caught between two cattle trucks and crushed beneath the wall of the cattle pen, death being instantaneous.

In 1892 another accident had occurred in circumstances which can only be described as unusual, to put it mildly. A passenger train, which had left Stroud at 7.55 a.m. was approaching Nailsworth station before its due time, when surprised staff saw it charge through the station, with full steam on, and end its journey against the stop, some 150 yards further on, fully embedded in coal and dirt. Luckily, although one coach derailed, no one was fatally injured, but one young lady, Lottie Tarrant, broke her leg and had to be taken to Stroud Hospital for treatment. The rather surprising end to this incident came at the enquiry, when it was found that the signals that warned approaching drivers of their nearness to the station had been removed some years previously! Needless to say the Company admitted liability and paid damages.

During the floods of 1889 a landslip occurred on the line at Rodborough, which required prompt action from officials to keep it open for traffic. A gang of men had to be engaged to clear away the fallen earth and debris in order to ensure that the traffic was not impeded. Flooding also occurred at the level crossing at Woodchester, causing passengers either having to go on to Nailsworth or walk back along the track to Workman’s (now Quaker Chemicals) to make their exit, which could only then be achieved by wading through a good depth of water. The ladies were favoured when those willing to entrust themselves to the strong arms of company servants were safely delivered to terra firma. The last train from Stonehouse to Stroud could not pass Ryeford and passengers were conveyed in a hired vehicle to Dudbridge before entraining there for the short journey to Stroud.

Finally, an indication of the rather high fares charged during the latter Cl9th can be seen from the following examples of excursion fares. In 1868 from Nailsworth to Birmingham, First Class cost 7/6d (37½p) and Covered Carriage 3/9d (18p) whilst to Bristol fares were 5/- (25p) and 2/- (10p), respectively. In 1936, however, fares seemed more realistic as the return fares from Dudbridge to Gloucester, Bristol and Birmingham were 1/- (5p), 3/- (15p) and 7/11d (40p).

Thus the story of the “Dudbridge Donkey”